Scientists believe they may have finally solved the mystery of how the 31 pyramids in Egypt including the Giza complex, were constructed over 4,000 years ago.

Also Read: Shanidar Z: Face of a 75,000-Year-Old Neanderthal Woman Reconstructed

A research team from the University of North Carolina Wilmington has made a discovery on the methods used by ancient Egyptians to build these structures.

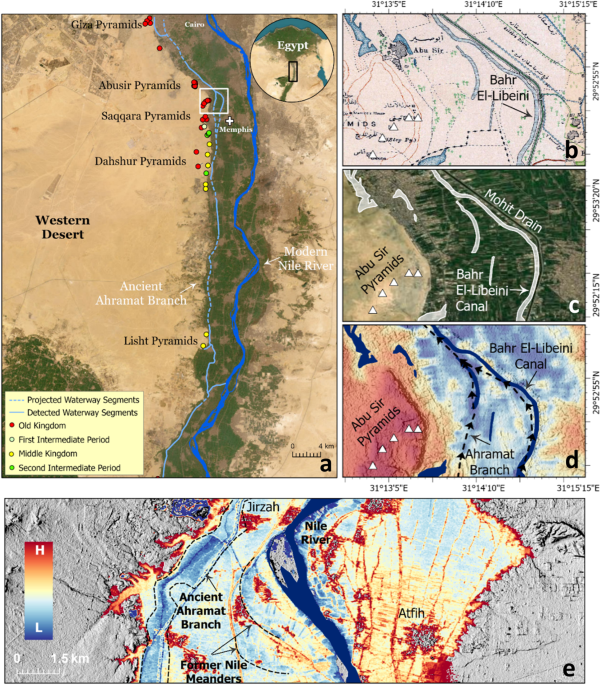

The team found evidence of a long-lost, ancient branch of the River Nile now buried under desert and farmland.

This discovery is with the theory that a nearby waterway was crucial for transporting materials like the massive stone blocks used in pyramid construction.

Prof. Eman Ghoneim, a figure in this research, explained that until now, the exact location, shape, size, and proximity of this mega waterway to the pyramids’ sites were unknown.

The team utilized advanced radar satellite imagery, historical maps, geophysical surveys, and sediment coring techniques to uncover this ancient river branch. They named it the Ahramat branch, which means pyramids in Arabic.

Allowed the team to penetrate the sand surface and produce images of hidden features. Helped in mapping the underground features. Provided evidence from samples that helped in reconstructing the ancient landscape.

The Ahramat branch was found to be approximately 64 kilometers (39 miles) long and between 200-700 meters (656-2,296 feet) wide.

This branch bordered 31 pyramids built between 4,700 and 3,700 years ago. The proximity of the river to these pyramids indicates that it was active during their construction phases.

Dr. Suzanne Onstine, a co-author of the study, addresses the importance of this discovery. She stated that locating the actual river branch and having data showing its use for transportation helps explain the pyramid construction process.

Ancient Egyptians likely utilized the river’s energy to move heavy blocks. The River Nile has always been a lifeline for Egypt and its role in ancient times was no different.

The discovery of the Ahramat branch helps explain the high density of pyramids between Giza and Lisht, an area that is now an inhospitable strip of the Saharan desert.

The river’s presence in the past would have made this region much more conducive to large-scale construction projects.

The study suggests that major droughts and sandstorms thousands of years ago likely buried this river branch under layers of sand. This shift would have led to the branch’s migration eastward and its eventual silting up.

The use of radar satellite imagery was particularly crucial in this discovery. It provided the unique ability to see through the sand and detect buried rivers and ancient structures.

This technology has opened new avenues for archaeologists to explore and understand ancient civilizations’ infrastructure and environmental adaptations.

A recent study led by Eman Ghoneim and a team of researchers published in Communications Earth & Environment (2024) reveals the role of a major extinct Nile branch named the Ahramat Branch in the construction and location of these structures.

Also Read: South Africa Marks 30 Years of Democracy Since the End of Apartheid

The study area spans from Lisht in the south to the Giza Plateau in the north. Early Holocene Environment (~12,000 years BP): The Sahara transformed from a hyper-arid desert to a savannah-like environment due to increased global sea levels post the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), creating large river systems and lake basins.

African Humid Period (AHP) (ca. 14,500–5000 years ago): Marked by heavy rainfall (300–920 mm/year), turning the Sahara into a habitable region while the Nile Valley was swampy and less hospitable.

Mid-Holocene (~10,000–6000 years ago): The Nile floodplain featured freshwater marshes, prompting human habitation along the desert margins.

Late Holocene (~5500 years ago to present): Increased aridity in the Sahara led to the migration of people towards the Nile Valley with settlements on elevated floodplain areas and natural levees.

The Ahramat Branch was identified through Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery and high-resolution elevation data.

The branch lies between 2.5 and 10.25 km west of the modern Nile, with a depth between 2 and 8 meters, a length of about 64 km, and a width of 200–700 meters. Segments of this branch were traced near the pyramids at Giza, Dahshur, and Lisht.

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and Electromagnetic Tomography (EMT) surveys along a 1.2 km profile revealed a hidden river channel 1–1.5 meters below the cultivated floodplain.

The channel is approximately 400 meters wide and at least 25 meters deep, matched the radar satellite imagery data.

Also Read: Lost Gustav Klimt Painting Sells for €30 Million at Auction

Two sediment cores (20 meters and 13 meters deep) were collected and analyzed. Core A: Found layers of brown sandy mud, gray sandy mud, black sandy mud, and well-sorted medium sand.

Core B: Similar findings with brown sandy mud, alternating silty and sandy mud layers, and well-sorted medium sand. The presence of clean, well-sorted medium sand indicated the former riverbed.

Causeways of several pyramids includes Khafre, Menkaure, Khentkaus, Pepi II, and Merenre, were found to lead to the banks of the Ahramat Branch or its inlets (Saqqara Inlet and Giza Inlet).

These causeways, terminating in Valley Temples likely served as river harbors. Evidence suggests that the Ahramat Branch was hydrologically active during the construction periods of Dynasties 3 to 13 (2686−1649 BCE).

Utilized European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-1 data with a C-Band SAR sensor, offering a penetration depth of 50 cm in dry, sandy soils.

Enhanced geospatial analysis with ENVI v. 5.7 SARscape software, generating geo-coded, orthorectified, terrain-corrected, and radiometrically calibrated images.

TanDEM-X (TDX) topographic data provided a fine spatial resolution of 12 meters, with a relative vertical accuracy of 2 meters.

The data helped identify subtle topographic features such as abandoned channels, natural levees, and river meander scars.

The study incorporated 1911 historical maps (Egyptian Survey Department scale 1:50,000) and combined them with radar and topographic data to trace the course of the Ahramat Branch.

A systematic grid-based survey using satellite imagery (Landsat 8, Sentinel-2) and TDX topographic data enabled the identification of ancient fluvial landforms and irregular ditches.

The Topographic Position Index (TPI) technique was employed to highlight riverbeds and meander scars.

Also Read: 3,400-Year-Old Stolen Statue of King Ramses II Returns to Egypt