When Penny Ashford’s father was diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s at age 62, she feared that the same fate awaited her. In her late 50s, her anxiety turned to panic when she began having trouble finding the right words.

“I couldn’t finish sentences. I couldn’t express myself clearly,” Ashford, now 61, recalled. “I remember sitting at a dinner party and not being able to finish my thoughts. It was the most surreal moment. I was terrified.”

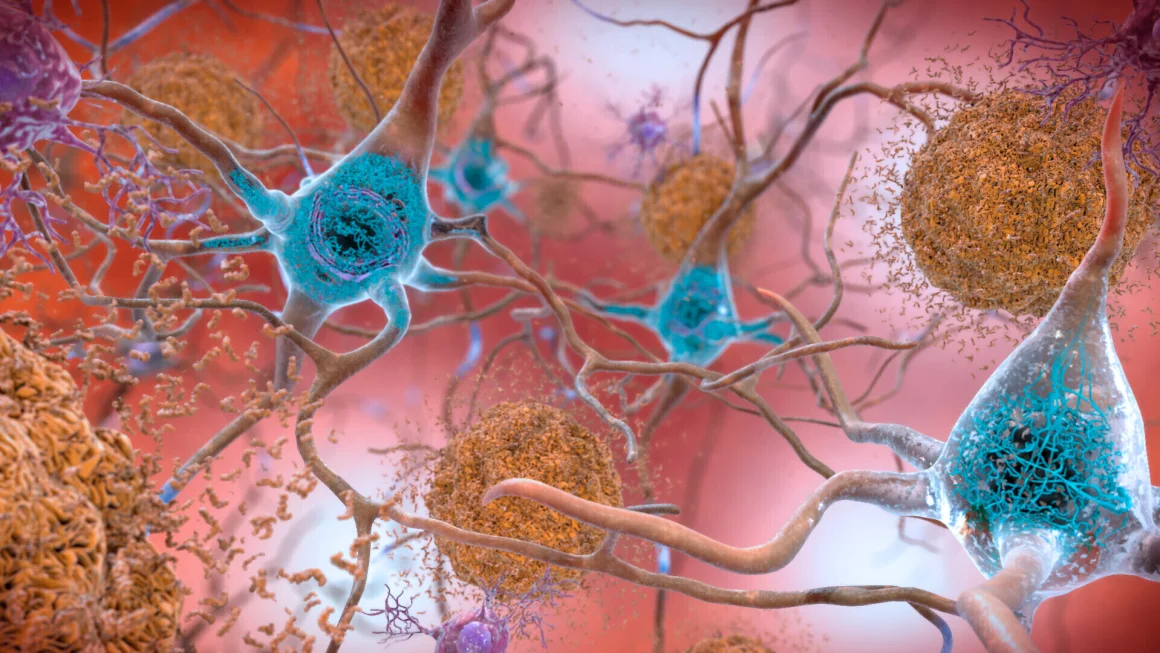

However, after making significant changes to her lifestyle, Ashford’s struggles with memory and speech have improved. She now sees a decline in amyloid and tau proteins—hallmarks of Alzheimer’s—as well as reduced neuroinflammation, all tracked through blood biomarkers used to help diagnose early-stage dementia.

Ashford is part of an innovative study monitoring her progress through blood tests. These tests are being explored as a less invasive, faster alternative to the spinal taps and costly brain scans traditionally used to diagnose Alzheimer’s. Presented at the American Academy of Neurology’s annual meeting in San Diego, preliminary findings from the study, which included 54 participants from the Biorepository Study for Neurodegenerative Diseases (BioRAND), highlight the potential of these blood tests for tracking Alzheimer’s risk.

Dr. Kellyann Niotis, the study’s lead author and a preventive neurologist at the Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Florida, explained that while biomarkers are already used to diagnose dementia, this study focuses on using them as outcome measures. “We want to see how these biomarkers change and track whether a person’s actions are positively affecting the progression of the disease,” Niotis said.

The Promise of Alzheimer’s Blood Tests

Alzheimer’s blood tests could be key to wider prevention efforts, experts say. By enabling earlier diagnoses in a doctor’s office, these tests could prompt lifestyle changes aimed at slowing disease progression.

However, according to Dr. Richard Isaacson, the senior author of the study, there’s still a lack of clarity regarding which blood tests are most effective for predicting or tracking the progression of Alzheimer’s. “The field is inundated with various tests, but there’s little consensus on which ones are most reliable for monitoring progression and response to treatments,” Isaacson said.

His team is working to identify and refine tests that could eventually function similarly to cholesterol tests, helping doctors track Alzheimer’s risk and progression over time. “In the future, people will likely get a baseline test in their 30s or 40s, and it will be used to monitor their brain health in the same way cholesterol levels are checked,” Isaacson noted.

Key Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

The study focuses on two crucial biomarkers: amyloid plaques and tau tangles, which are central to the development of Alzheimer’s. Amyloid plaques form in the brain and disrupt nerve cell communication, while tau tangles are believed to contribute to memory issues. Blood tests for biomarkers like plasma phosphorylated tau (p-tau217) are considered highly effective for diagnosing early stages of Alzheimer’s.

Dr. Maria Carrillo from the Alzheimer’s Association described p-tau217 as a “beautiful marker for Alzheimer’s.” Elevated tau levels in the brain, she noted, are a clear sign of dementia, and these biomarkers can also help distinguish Alzheimer’s from other types of dementia.

Additionally, tests measuring the amyloid 42/40 ratio and neuroinflammatory markers like glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and neurofilament light chain (NfL) are used to track Alzheimer’s progression. These tests, combined, can give a comprehensive picture of a person’s brain health and risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

Personalized Approaches and Results

The BioRAND study’s participants received personalized lifestyle recommendations to improve brain health. These included strategies to manage blood pressure, improve diet and exercise, reduce stress, optimize sleep, and address metabolic and hormonal imbalances. The interventions, tailored to each individual, were shown to improve cognitive function by up to five points on a cognitive test for those with mild cognitive impairment.

Ashford, for example, radically changed her habits. She eliminated sugar from her diet, stopped eating sweets, and began a rigorous exercise program including cardio, resistance training, and yoga for stress reduction. She adopted a plant-based Mediterranean diet and worked with her doctors to tailor her supplement regimen. “I gave it 110%,” Ashford said. “I lost 30 pounds and built lean muscle. It was incredible.”

After one year, Ashford’s blood markers showed remarkable improvements. Her p-tau217 levels dropped by 43%, and p-tau181 decreased by 75%. Additionally, her GFAP levels decreased by 66%, and neurofilament light chain dropped by 84%. These reductions in brain inflammation and neurodegeneration correlate with improvements in her memory and speech abilities.

Moving Forward

Isaacson and his team were impressed by the results across the study group. Even participants with lower levels of compliance showed improvements in their biomarkers. “Every time we see these markers trend in the right direction, it amazes me,” Isaacson said. “For years, we were told that this kind of progress was impossible, but now we’re seeing it firsthand.”

While much work remains before blood testing becomes a standard part of Alzheimer’s diagnostics, Isaacson remains optimistic. “We’re being careful not to overpromise, but the progress is real,” he said.

For Ashford, tracking her biomarkers has been a huge motivator. Reflecting on her father’s decline, she is grateful for the opportunity to take control of her brain health. “I’m so proud of what I’ve achieved,” she said. “Looking at my dad, who didn’t have any of these options, I feel so lucky. We’re lucky.”